“Will you pray for Gary and others who find their mission field among people serving time in these concrete jungles? Pray that hardened hearts would be transformed. Pray for homes that have a vacant seat at the dinner table.”

Decades ago, when one felt “called” to the mission field, the pull was most often to a distant land. As a young girl, I recall hearing stories of Mark and Huldah Buntain and their ministry to the poor in Calcutta, India. In my teenage years, church services included times where PAOC missionaries would visit and share what God was doing in Africa, India and Central America. I would return home after those mission services and go straight to my Encyclopaedia Britannica books to check out maps and pictures of people groups and places where others were passionate about taking the gospel.

Most recently, my heart has been drawn to stories of those called to mission fields much closer in proximity and which look much different. They are found across our nation and are separated from the outside world with concrete, electronic gates, iron bars and barbed wire—our Canadian prisons.

Not long ago, I heard the story first-hand of how Gary Reynolds answered God’s call on his life more than 30 years earlier to take the message of Christ to people held in these institutions. As one of the early chaplains with The Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada, Gary speaks with experience when he says, “Everything you see portrayed on television is true, if not much worse. Gangs, drugs, violence, corruption, brokenness, emptiness, despondency, profanity … it is a very hard place.”1 Yet, in the middle of the despair and darkness, there is often a quiet oasis. The chapel, a temporary “spa for the spirit,” offers a small sliver of solace for the troubled soul.

This “oasis” can be visited, but only after a request is made and permission granted, with all protocols in place to ensure the chaplain’s safety and security. Gary recounts how many inmates come to this “sanctuary” looking for quiet and, while there, often reflect with him about their times in Sunday school in their younger years. Sadly, those years were followed by poor decisions and hardened habits that changed the course of their lives. For some, the change was just for a season; for others, it was for life.

Jay is one of the inmates Gary was able to minister to. Jay was a young man of promise who made wrong choices that led him to a life of incarceration. Looking for peace, answers and solace for his tormented soul, Jay requested a pass to visit the chapel. In their initial conversation, it was clear to Gary that Jay was a man who was indifferent toward others and callous to the consequences of his own actions. But, through prayer and godly counsel, Jay’s tough exterior began to soften, and over time he encountered true forgiveness and the transformational power of Jesus Christ. In Gary’s words, “It is an extremely difficult endeavour to follow Jesus ‘in the garbage dump.’ Prisoners do not have access to the Internet or endless books to aid them on their spiritual quest. But they do have access to a Bible and to the equipping power of the Holy Spirit, as they hold on to hopes and dreams.”2 Whenever Jay leaves the serenity of the chapel, there is no escaping the harsh reality of his surroundings, yet he tries to read his Bible and follow God’s ways to the best of his ability. He believes it is only by God’s grace that he is alive today. Jay’s newfound freedom in Christ has given the life sentence he is serving a whole new perspective: he no longer serves it alone, and he knows a much greater life is ahead.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the highlight of Gary’s weeks were Sunday nights. Forty-plus inmates and ministry workers would assemble, singing songs like “One Day at a Time,” “Amazing Grace,” and “Because He Lives.” Gary describes it as a “beautiful, off-key mess”! Real and raw tough guys would worship God together, be encouraged by the Word, and be prayed for—a fortifying experience to help them endure their confinement for another week.

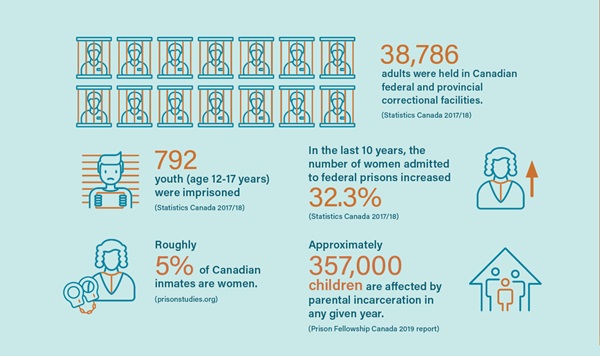

Canada’s incarcerated populations are most often linked to families who are affected both by their life choices and by their absence. The impact on the family unit is heartbreaking and often destructive. According to Statistics Canada, 37,786 adults and 792 youth (aged 12 to 17) find their home in Canada’s federal and provincial prisons. In the last 10 years, the number of women admitted to federal prisons increased by 32.3 per cent. Sadly, 357,000 children in Canada are affected by parental incarceration—a number that compares to the entire population of Halifax, N.S. (Prison Fellowship Canada).

Gary has experienced many highs and some very heart-wrenching lows in his work over the years. There is sorrow but also great fulfilment in seeing firsthand the transforming love of God at work in the hearts of the people he meets.

Will you pray for Gary and others who find their mission field among people serving time in these concrete jungles? Pray that hardened hearts would be transformed. Pray for homes that have a vacant seat at the dinner table. And pray that more individuals like Gary would respond to God’s call to bring the light of Christ to dark places … because we must!

Corinne Storms is part of the Mission Canada core team and oversees Wordcom Christian Resources, the distribution arm of The Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada.

- Gary Reynolds, telephone interview with author, September 18, 2020.

- Reynolds, telephone interview.

This article appeared in the January/February/March 2021 issue of testimony/Enrich, a quarterly publication of The Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada. © 2021 The Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada. Photo by Grant Durr on Unsplash.